Covid-19 forces us to stay at home and, inevitably, muse about the near future. Let’s blow away the cobwebs for a moment and travel in mind: with Nancy Campbell (42), a Scottish poet. The writer takes us with her to the coldest regions of our planet: Iceland, Greenland, Denmark, Scotland, Switzerland and the Arctic. Her poetry reveals the mysteries of ice – an endangered wonder. Read on!

“There’s an Arctic myth that tells how before the sun came into being, ice could burn. People used ice to fuel their lamps, because no one could go hunting in the dark. Tonight the sea ice is luminescent, and mysterious objects glow by the shoreline in the twilight, their shapes distorted and concealed under snow. It will be weeks until the spring thaw, and sunshine, reveal what they are.”

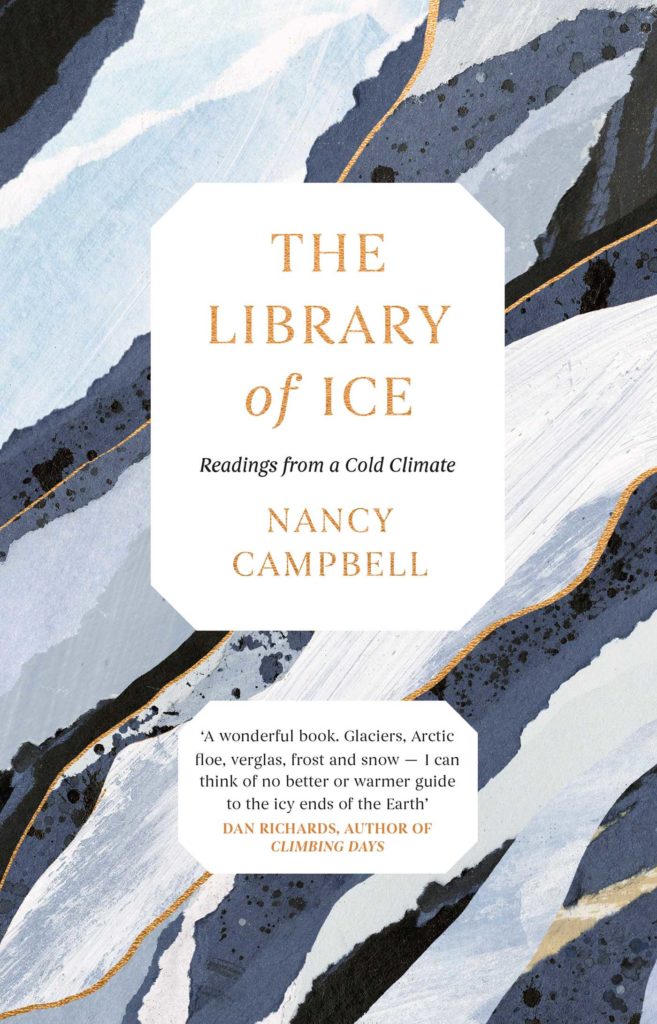

The Library of Ice (extract), Nancy Campbell

Nancy, you have lived and written in the coldest regions of our planet. From there, you bring a message to the world: the meaning of ice, not only as a phenomenon, but as a strong ecological factor. How do you feel now, regarding the changes in nature?

There are catastrophic changes facing our ecosystem, with the melting icecaps just one threat among many. Warnings from scientists have become ever more sobering in the decade since I first travelled to the Arctic. Policy change has been minimal at best. The apathy of governments and business in the face of climate crisis is terrifying. But I see a few chinks of hope. Environmental issues are now widely reported in the media, rather than being a special interest story. The new voices advocating for the planet are emerging from the #FridaysForFuture movement. The next generation is demonstrating that it has the bravery, energy and imagination to tackle the grave challenges that lie ahead.

Can you recall the first time ice began to reveal its fascination for you? Where was it?

I grew up in isolated hamlets in the Scottish Borders during the notoriously bitter winters of the late 1970s – one year even known as ‘The Winter of Discontent’. The natural world had a deeper influence on me than the few people I met. There’s an endurance, and a necessary solidarity between humans and other creatures in the cold that I find very alluring. I’m also intrigued by the converse: the temporality of ice, its fickleness. Ice is so strong that it can break apart huge rock formations. In doing so it has determined the shape of our world. Yet at the same time it is extremely sensitive. With incremental degrees of temperature change, it becomes liquid and flows away.

But my thoughts about ice were tenuous until I arrived on the island of Upernavik. I had a flight up the west coast of Greenland in a Twin Otter plane in a wild snowstorm. This gave me a sense of how perilous the Arctic weather could be. I didn’t expect to survive the journey. There were few flights to the island. I discovered that the inhabitants were more trapped than usual. Until recent winters, it had been possible to walk across the sea ice to reach other places. But the ice had become unpredictable and unsafe to step on. There had been fatalities. My desire to learn more about ice was driven in part by social concerns. I was aware of the impact that its disappearance was having on people’s freedom to travel and pursue traditional practices of hunting and fishing.

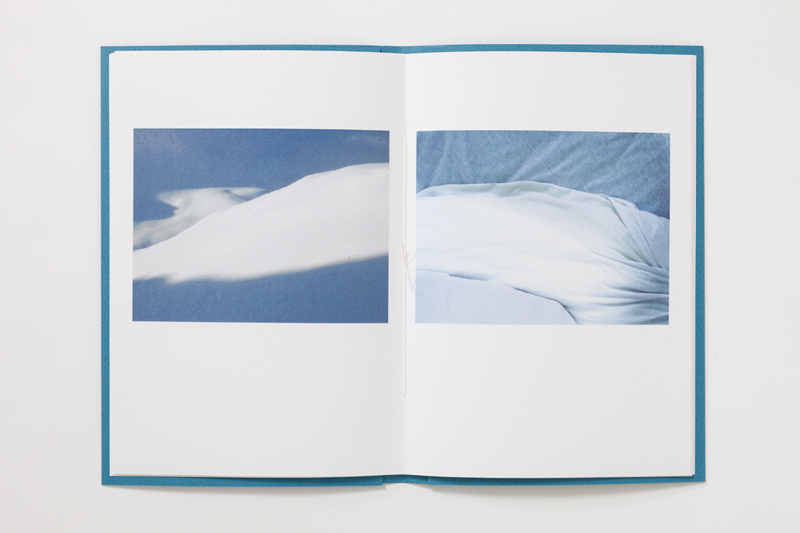

Inuit religion is animist, ascribing life to all things whether human or animal, rock or ocean. And the ice in Greenland does seem to be alive: a dynamic, mutable entity. While living on Upernavik, every morning I made a one-minute film of the sea ice in front of my cabin. Day after day it was different. I saw everything from grease ice as it began to form from frazil crystals to thick flat rounds of pancake ice. I’ve always been fascinated by the material nature of objects, whether seen through the lens of visual culture or scientific research. While writing The Library of Ice I enjoyed reading seventeenth-century natural scientists’ work on cold. For example Robert Boyle, who made ground-breaking investigations of ice, despite never having sufficient glass vials or cold enough weather. However, my data is as much literary as scientific. The ink well is my test tube.

Writing in the cold regions – how would you describe it?

I travel to places where I can embed myself for a month or more. I go to find a home, not a portable tent like the first polar explorers. When I first travelled north, I did so partly because housing in the UK was prohibitively expensive on an writer’s income. I was working as an antiquarian bookseller. I was writing in all the hours I was not at work as well as in some of those during which I was. Increasingly I needed more time for my own projects.

So as well as a research interest, my move to the cold regions was for reasons of economy and ecology. And rather than being a challenge to the writing it enabled it – giving me much valued time and shelter.

Nancy Campbell

While writing The Library of Ice I discovered that the etymology of eco lies in the Ancient Greek οἶκος (‘house’ or ‘home’). It is a word which also underlies ‘economy’.

I lived nomadically during these years. I’d put all my possessions in storage, and didn’t have a base from which to operate. The residency programmes I have embarked on allowed me to spend a few months in one place. I was undisturbed and – most importantly – able to focus on my work. I stayed in unoccupied log cabins, museum box-rooms, and out-of-season hostels. Some settings have been grander. I researched the Alpine sections of The Library of Ice in an architect-designed pod, suspended in mid-air at the foot of the Jura mountains in Switzerland.

Credits: Leo Fabrizio for Fondation Jan Michalski, Montricher, Switzerland

I often worked in close partnership with an institution. Thus I find accommodation in exchange for a close engagement with the collections and a commissioned work. This was the case in Denmark. Here, I created the installation Ljimford Lines for Doverodde Book Arts Festival and a sequence of short texts about the region, Doverodde.

Almost everywhere I have been fortunate to call home for a while there has been a library, and reading gave me an introduction to the place. This was especially true of Upernavik Museum in Greenland where the Greenlandic-English dictionary took on talismanic significance for my work. And then there’s remote research and voyages of the imagination, time spent reading all I could about ice and snow in libraries in the UK.

My work is observation and conversation. I go walking, even short distances, to get to know the landscape and my neighbours. The snowdrifts were so deep on Upernavik that I could only walk to the harbour and to the cemetery. Instead of long hikes, I saw incremental changes to the same places over time. I liked it that way. It’s the reason I feel uncomfortable with the description of “travel writer”. It suggests continuous movement, whereas really I am interested in gaining a deep understanding of one place. Hence the ice films on Upernavik: close looking means more to me than long explorations.

The glaciers and icebergs I’ve seen have been momentous and memorable. But it’s often the commoner forms of frozen water that fascinate me most. I think of the icicles hanging from the eaves in Siglufjörður, a harbour town in the north of Iceland.

Nancy Campbell

Those icicles changed daily. Their length was a way to gauge the level of snow melt from the corrugated iron rooves. Water arrested during its journey to the ground. When I left town in April, the icicles had finally gone. In this way the ice recorded the passing of time and season, and my own tenure in Iceland too.

How did ice as an element present itself to you each time you had it around you for longer?

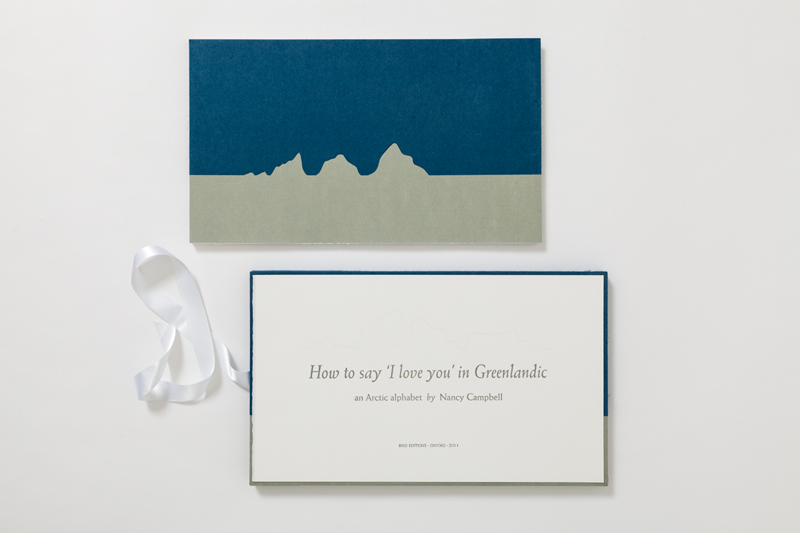

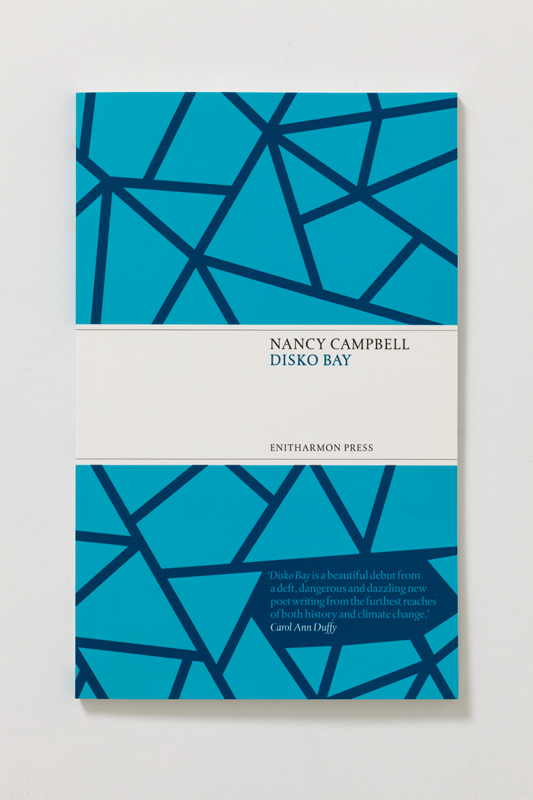

I’ve produced work in different media, according to place and the demands of certain commissions. My first book How To Say ‘I Love You’ In Greenlandic, was a large format, letterpress alphabet book. It comes with laboriously printed and colourful pochoir prints of icebergs. I was drawn to the idea of applying the same recherché process to recording icebergs that had once been used by fashion houses in 1920s Paris. Later, I worked in photography. I made books such as ITTOQIPPOQ and Vantar|Missing, which both incidentally refer to textiles. The former looks at laundry freezing on washing lines in Greenland. The latter explores the avalanche-prone slopes above the town of Siglufjörður. These visual explorations have always been accompanied by essays and poems. Recently I have focussed on non-fiction, The Library of Ice.

What is the link between ice and poetry for you?

The key “library” in The Library of Ice is not human-made. I talked to cryologists, who read the Earth’s history by drilling enormous ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica. These are sliced into wafer-thin discs, and then stored and analysed. They contain layers of microscopic debris and chemical traces, which reveal details of past climate going back centuries. The intricate elements of this process – and the care with which it is pursued – intrigued me. It did so in the way bookbinding and printmaking does actually: the material creation of a story. Scientists even use a poetic term to describe alternating summer and winter ice: the relative density, the “depth-slab/wind-hoar couplet”. Like the closing lines of a sonnet.

The synergy between language and landscape, and the metaphor of landscape-as-book is not new. I found the Scottish naturalist John Muir writing ecstatically in his Travels in Alaska (1879) of glaciers like the “pages of a book”. I suppose the poet in me was curious: How far can this metaphor be stretched? What implications would it have in other contexts? How does it play out in an era of climate crisis, in which there is no longer the hope of leaving permanent records, since the future of the planet is not secure? I bring these ideas together in the poem “The Vostok Ice Core Gives a Creative Writing Lesson”.

The ice core itself is speaking in a series of rules, such as “Be complete. Tell the whole story: every day in every season, summer and winter, from the present until the beginning of time.”

Which of the northern places did you like most?

I’ve been very fortunate to travel and be made welcome in many places. Each very distinctive, and I can’t say I ever had a favourite. I have a disposition which leads me to believe I am always most in love with the place where I currently find myself. But the country I would happily go back to and never leave would be Iceland. It is a place which as a whole I found immensely satisfying. I love the steaming sulfur pools, the mountains, the centrality of storytelling in the culture. I like the people, the characteristic mix of cordiality and reserve.

There’s one valley, Fljótsdalur, where I stayed during September and October. This is the time when the sheep are brought down from the hills. It’s where one of Iceland’s most famous novelists, Gunnar Gunnarsson, lived and built a very unusual stone house. It is now a museum with a residency programme for writers. I was there while I was completing the manuscript for The Library of Ice. So I spent a lot of time at my desk. I’d like to go back in mushroom season, walk further along the paths I only just began to tread, to take off up into the hills with a notebook for days on end.

You have been living in Bamberg, Germany as artist in residence since 2019. Tell me more about it!

I have been in Bamberg since April 2019 and return to the UK this spring. I’ll be back for readings in Berlin (Haus für Poesie) and Munich (Schamrock Festival in October). Villa Concordia has been a productive and peaceful residency in an almost unsettlingly beautiful 17th-century water palace on the River Regnitz. We were 13 writers, artists and composers. I’ve been working on a book about snow around the globe, a follow-up to The Library of Ice. It will be published by Elliott and Thompson this year. Also, continuing work on a sequence of poems about rivers. It began while I was Canal Laureate in the UK last year.

Most of my residencies have been one season or less. So it’s been a great privilege to be funded to stay in Bamberg for almost a year. The opportunity to settle, and observe a location change through the full cycle of the seasons has had a real impact on the way the work develops. And at a time when the UK Government is – tragically, I believe – turning its back on Europe, it feels very precious to have this time to discover the work of my German colleagues.

The Künstlerhaus was the Bavarian state chemistry institute during the twentieth century. On the exterior of the Künstlerhaus there’s a plaque that mentions the chemist Walter Noddack, and crediting the discovery of Rhenium to him alone. I wanted to pay homage to Ida Tacke (later Noddack, after she and Walter married), one of the first women to study chemistry in Germany, and part of the team that discovered Rhenium. She also suggested the possibility of nuclear fission, and was nominated for the Nobel Prize three times. My poem “How to Discover an Element” is a celebration of Ira’s life, and acknowledges the importance of artistic and scientific collaboration.

Are your works available in German?

Yes, there are the following available so far:

- Some recent poems and an extract from The Library of Ice translated into German by Hans Jürgen Balmes are available in the journal Neue Rundschau.

- Bamberg has crept into numerous essays and poems I’ve written this year, perhaps most strikingly Concordi.A., the Künstlerhaus magazine (see Instagram).

Thanks, Nancy! Stay healthy these days!

0 comments on “Authors | How to read ice? Scottish poet Nancy Campbell and her Arctic literature”